An Eye in the Head of a Poet

A film is never really good unless the camera is an eye in the head of a poet.

—Orson Welles

I have loved movies my whole life. For many years in my youth, I wanted to be a filmmaker, and an actor, and I spend much of my free time watching movies. My best cinema years were when I lived in Paris, I went to the movies several times every weekend, and loved all the options for films from all over the world. When I lived in Salt Lake City, I got to attend the Sundance Film Festival, and see so many wonderful films, and screenings of all the Oscar-nominated movies that were (before streaming) harder to see, like the short films and documentaries and foreign films.

When Netflix opened, it was thrilling to have access to so many films. Finally I got to watch movies I’d only heard about, particularly queer films, and documentaries. I still think about some of the movies I watched in my dorm, and the glee at seeing those DVD envelopes in my mailbox on campus.

One thing I love about film is the way silence can function like white space on the page of a poem. Someone on last night’s Academy Awards telecast likened films to novels and short films to poems, which I think is apt, but I think film in general is a medium much akin to poetry; or at least it can be.

My Intro to Lit class is currently studying poetry, and as they grapple with the genre, it’s been interesting to hear them make comparisons. The obvious, to music, paintings,

The film Women Talking won an Oscar last night for screenwriter Polley, and while I still think that She Said ought to have been nominated as well, I’m very happy about this win. It’s an adaptation of the book by the same name, by Miriam Toews, who described the novel as “an imagined response to real events" that took place on the Manitoba Colony, a remote and isolated Mennonite community in Bolivia. The inciting incident that inspired the novel is a horrifying case. Between 2005 and 2009, over a hundred girls and women in the Mennonite colony woke up to discover that they had been raped in their sleep. These nighttime attacks were denied or dismissed by colony elders until finally it was revealed that a group of men from the colony were spraying an animal anesthetic into their victims' houses to render them unconscious. Toews' novel centers on the secret meetings of eight Mennonite women who, on behalf of the other women in the colony, must decide how to react to these traumatic events. They have only 48 hours before the colony men, who are away to post bail for the rapists, return.

It’s a beautifully-written and heartbreaking novel, and the screenplay differs, but does it justice. It’s an apt win for the film, since, while visually beautiful as well, has its script as its greatest strength. The acting is strong as well. It’s a fantastic ensemble cast, with Rooney Mara, Clare Foy, Frances McDormand, Jessie Buckley, and Judith Ivey, and the title Women Talking is suitable as the majority of the film is dialogue between this group of women.

“We are wasting our time by passing this burden, this sack of stones, from one to the next, by pushing our pain away,” the charter Greta (played by Sheila McCarthy) says. There’s a sparse beauty to the film’s language and cinematography, even as the subject matter is horrifying. Yet the poetry of Polley’s images (shot by Luc Montpellier), show the beauty of life in the colony. Shots focus on the women’s hands—drawing, braiding hair, sewing and weaving, tending to children.

Greta frequently tells parables featuring her horses, Ruth and Cheryl, as examples for what she believes the women ought to do, and while the other women grow exasperated every time she brings up the horses, the metaphors are powerful. A score by Hildur Guðnadóttir sets a powerful tone to the film.

The other award for screenwriting at last night’s Oscars went to Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert for the original screenplay of Everything Everywhere All At Once. I’ve written briefly about the film before, but I was so happy to see this weird, wonderful, heart-full conceptual film sweep the night and receive so many well-deserved accolades. It’s become one of my top 5 films of all time, and it gives me hope whenever something so well-done is recognized for how genius it is. Seeing the joy of both the winners at the awards ceremony and everyone else’s joy for them was delightful.

The creators reportedly ruminated on their out-of-the-world concept for nearly 12 years, and that time spent perfecting it really comes through. The film moves fast, and it’s easy, on a first watch, to miss things, which is why multiple viewings are rewarded with a deeper understanding and appreciation. I’m a slow writer, and it takes me years, as well, to develop the concepts for my projects. My last book was published in 2016, and I’ve just now begun to really work out what I want to do for my third book. Sometimes everything falls into place swiftly, but I think when a project is rushed, it’s evident in the final product. EEAAO is a masterpiece of craftsmanship on every single level, and the time spent developing it paid off.

The depth of relationships displayed in the movie, from the focus of mother and daughter, husband and wife, to the exploration of the multiverse where, in one incarnation, Michelle Yeoh’s character is married to Jamie Lee Curtis, her tax auditor in the main storyline. One of my favorite of the multiverses is one in which Yeoh and her daughter, played by Stephanie Hsu, are boulders on the edge of a cliff, yet the maternal bond remains.

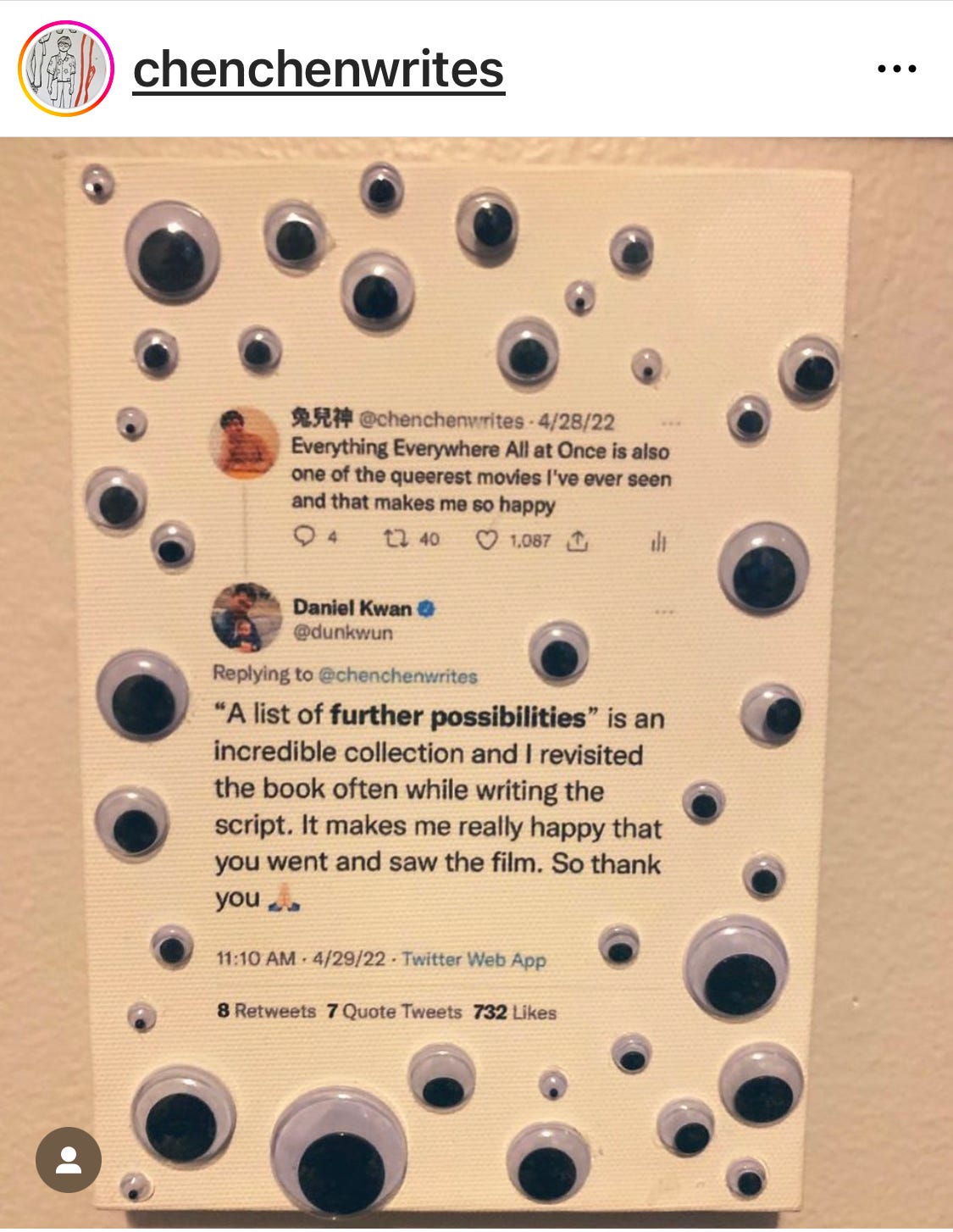

One of my favorite contemporary poets, Chen Chen, shares my love of this film, and shared this i’mage of a tweet exchange with the filmmakers, who love his work and relied on it as they crafted EEAAO:

I’m not surprised to learn that poetry partially inspired the film, as it feels so poetic, and When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities pairs so well with the film, as it’s focused on family, love, the difficulties of maternal relationships, and the immigrant experience. I read the poetry collection in one sitting soon after it was released, and I’ve revisited it many times. Chen Chen is also just one of the kindest poets I’ve met, the kind of person (much like the Daniels), who you root for to succeed, not only because their talent deserves it, but because they are such good people, you want that recognized as well.

I admit that I avoided watching EEAAO for months, because I don’t particularly like action movies, but the more friends lauded the film on social media, the closer up it inched on my watch list. I expected to like it based on what trusted friends said, but I wasn’t anticipating the emotional resonance, nor how the movie would stick with me. The chain of events portrayed in the movie comes from a place of self-reflection and the decisions we make, which shape us into the person we are today. The film also encompasses themes of infinite universes, all of which are determined by the paths we take. As I’m currently in a transitional moment myself, determining what my next steps in life are, it feels particularly resonant.

The film also deserves credit for rejuvenating the careers of the parties involved. Before the movie’s release, perhaps only Jamie Lee Curtis among the cast could realistically be called ‘superstar.’ But over the past year, Yeoh, Hsu, and Huy Quan have been catapulted into stardom and shown no signs of slowing down. Seeing Huy Quan (whose first roles were as Short Round in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Data in Goonies) embrace Harrison Ford, who presented the Best Picture Award had me in tears.

He also gave the most moving acceptance speech of the night when he was awarded Best Actor in a Supporting Role (though he deserved to be in the Best Actor category).

Finally, I loved The Fabelmans, Steven Spiellberg’s semi-autobiographical film that captures his early life discovering filmmaking and his mother, played by Michelle Williams. I was a bit surprised it didn’t win any awards, because it was a stunning portrait of a creator’s early development that really accurately portrayed what it is like to feel a calling as an artist, and how hard one will work at innovating and chasing that dream. We get to see Sam Fabelman as a young boy seeing a movie for the first time (the Cecil B. DeMille 1952 circus drama The Greatest Show on Earth), and his growing obsession with making movies to one of the final scenes when he gets two minutes in the office of his favorite director, John Ford (played by David Lynch), who gives him some brilliant advice and then kicks him out.

At one point in the movie, Sam’s mother Mitzi (a concert pianist) says their family is divided into the scientists and the artists, and she and Sam are the artists. This is a film about the struggle to be an artist and fight against external pressures (from parents and society) to be more traditionally successful, and how that, ultimately, can lead to despair. Though, of course, throughout it all, we have hope, knowing “Sam” in the film becomes Steven Spielberg, one of the most successful filmmakers of all time.

In the film, Sam stops making films for a few years, for reasons I won’t spoil, and though this did happen to Spielberg, he revealed in an interview that the real reason he gave up for awhile was different.

“I had a crisis of confidence after seeing David Lean’s epic Lawrence of Arabia. When the film was over, I wanted to not be a director anymore because the bar was too high.

“I had such a profound reaction to the filmmaking, and I went back and saw the film a week later,” he added. “I saw the film a week after that, and I saw the film a week after that, and I realized that there was no going back. This was going to be what I was going to do or I was going to die trying.”

I can relate to that so much. Some books galvanize me to write, while others make me want to abandon the pursuit entirely. Yet I keep coming back, as most artists do, because we simply can’t help ourselves.